At the CAPS International Conference, Marcus Rodriguez treated our workshop to an entertaining, enlightening and encouraging gallop through Dialectical Behavioral Therapy, focusing on “radical acceptance” – one of the many skills DBT uses. This therapy is under the cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) umbrella. It was originally created to help with borderline personality disorder. Now it is used to help with a variety of other conditions. It is a very organized way to teach people to change when their behavior is damaging relationships and even threatening to destroy them.

DBT teaches clients four sets of behavioral skills under the headings: mindfulness; distress tolerance; interpersonal effectiveness; and emotion regulation. But, whether we are ill or not, as Marcus demonstrated, we can all benefit from adapting and incorporating the skills into our lives.

Christians use DBT, Buddhist-leaning or not

For some people, applying DBT skills might seem sketchy, since many of the skills are straight from the Buddhist playbook. You might know that I’ve suggested elsewhere how Christians can be friends with Buddhists. But appreciating the strengths of Buddhist or DBT philosophy doesn’t mean we overlook the core elements that could undermine our faith in the name of reducing our suffering. There isn’t much in any psychotherapy models which a Jesus follower wouldn’t need to adapt.

DBT represents some of the real differences between Jesus and Buddha. The Buddha said, “Look not to me, look to my dharma (doctrine).” The Christ said, “Follow me.” The Buddha said, “Be lamps unto yourselves.” The Christ said, “I am the light of the world.” Yet contrary to the original intentions of both, some later Buddhists (the Pure Land sect) divinized Buddha. And some later Christians (Arians and Modernists) de-divinized Christ.

Peter Kreeft sums up the differences nicely. He says,

On this crucial issue—the diagnosis of the human problem—Christianity and Buddhism seem about as far apart as possible. For where Buddha finds our desires too strong, Christ finds them too weak. He wants us to love more, not less: to love God with our whole heart, soul, mind and strength. Buddha “solves” the problem of pain by practicing spiritual euthanasia: curing the disease of egotism and the suffering it brings by killing the patient, the ego, self, soul or I-image of God in humanity.

No Christians using DBT think they are doing this, I suspect. But the modality comes from that playbook.

It is easy to say that many Christians are better Buddhists than they are Jesus followers, since they practice law-keeping designed to squash their desires before they result in sin, often at the cost of their soul. They kill their souls in order to not face the shame of needing new life. It would be better if they followed the Buddha’s example and sat under a tree until they were enlightened – that is, enlightened in the way Paul hopes: that

“the God of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of glory, may give to you a spirit of wisdom and of revelation in the knowledge of Him. I pray that the eyes of your heart may be enlightened, so that you will know what is the hope of His calling, what are the riches of the glory of His inheritance in the saints” (Ephesians 1:17-18).

In that same hope, I offer three DBT skills that everyone could practice that will increase our capacity to gain a spirit of wisdom instead of rolling around in our unquestioned behaviors that lead to sin and ruptured relationships.

Mindfulness

Finally, brethren, whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is of good repute, if there is any excellence and if anything worthy of praise, dwell on these things. – Philippians 4:8

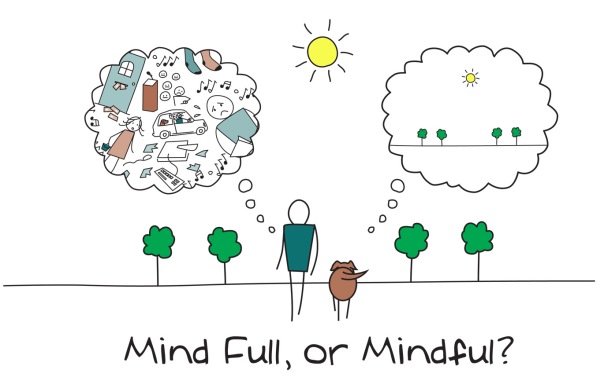

“Mindfulness” has a lot of definitions. For Marcus, it begins with stepping back from your normal thinking pattern and noting how you are enacting the pattern. That’s also known as mentalizing. Other teachers say mindfulness means living one’s life more in the present moment, instead of allowing oneself to be hijacked by the past and the future.

Marcus instructed us to bring to mind a situation about which we felt deeply, but which was not changing and not likely to change because of something we could do to change it. We closed our eyes, or stared at a focal point, breathed in and then breathed out the sentence we had constructed to describe the situation. We were told to simply note the fact when our minds wandered, thank ourselves for noticing, and return to our practice.

Our teacher was helping us to get a feel for how we could step back and look at automatic behaviors we need to change using this crucial DBT skill. For instance, if you’re entangled in your thoughts, you might think/feel: “Susan is really nice. She’s such a great person. I wish I were more like her. I should ask her if she wants to go for coffee sometime. I’d like to get to know her better.” Being mindful, you get some space to reduce the extraneous thoughts and observe, “There’s a thought that Susan is such a nice person.”

We would all like to pause, check in, identify our emotions and consciously make healthy decisions. Try it. It might surprise you just how little you are thinking and feeling about what you are actually thinking and feeling. This mindfulness is a lot like what Paul is suggesting to the Philippians, isn’t it?

Reality Acceptance

May the God who gives endurance and encouragement give you the same attitude of mind toward each other that Christ Jesus had, so that with one mind and one voice you may glorify the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ. Accept one another, then, just as Christ accepted you, in order to bring praise to God. – Romans 15:5-7

This skill focuses on accepting our daily experiences and working to accept the more painful events that have happened. Marcus had many colorful examples about how fighting reality only heightens our suffering, like, “Beating up your pillow all night does nothing but make the bed sweaty.” He had a ready excuse to practice this skill during our workshop, since he needed a projector and was not provided one. That reality frustrated and embarrassed him. He said, “Instead of telling myself, ‘My life sucks’ I have to remind myself ‘It is what it is. I will get through it. Breathe.’”

This spirit of acceptance is what Paul recommends to the Romans as they face the divisions in their church. But it also applies to accepting the divisions we feel in ourselves. DBT requires a hard won discipline of living in whatever is materially real in the moment, free from desires and guilt. For Jesus followers, a grateful acceptance of being accepted by Jesus is required, but the results are similar, I think. Our faith is constantly accepting God is with us in Jesus, and accepting that controlling our desire to control cannot really save us. Faith is cooperating with the One who can save us!

Nonjudgmental Stance

But with me it is a very small thing that I should be judged by you or by any human court. I do not even judge myself. I am not aware of anything against myself, but I am not thereby acquitted. It is the Lord who judges me. Therefore do not pronounce judgment before the time, before the Lord comes, who will bring to light the things now hidden in darkness and will disclose the purposes of the heart. Then each one will receive commendation from God. – 1 Corinthians 4:3-5

Marcus was concerned that we learn the difference between a judgment and a fact. Negative judgments tend to boost our emotional pain. So when we’re angry, irritated or frustrated, we should pay attention to what judgment we are making or we will just make things worse. “I hate Philadelphia because it rains so much” is different from “I had hoped it would not rain today.” “My partner is an idiot,” is different from: “I worked another long day and when I got home my partner asked, ‘What are you making for dinner?’ I am angry about this and disappointed he’s not making an effort to help.”

Being less judgmental doesn’t eliminate our pain, but it might take it from an 8 to a 5. If we practice the “radical acceptance” Marcus was teaching us, we might move the needle from 5 to 3. Radical acceptance does not mean agreeing with what happened, or approving, excusing, absolving, allowing, resigning, or wallowing in suffering. Radical acceptance simply means we acknowledge the facts of our lives without judgment — we often fight reality instead. That fighting only intensifies our emotional reaction. We might fight reality by judging a situation, saying “It should or shouldn’t be this way,” or “That’s not fair!” or “Why me?!” Fighting reality only creates suffering. DBT people say, “Pain is inevitable in life; suffering is optional.”

The idea we can choose our way out of suffering is where we see how much Buddhism impacts DBT. It leans toward shutting down the desires and leading us to find a place of nothingness where “should” or “want” is irrelevant. For disordered people, this ability is priceless — and most of us could use a dose.

But we do not need to adopt the core premise of Buddhism to make use of skills that help us pay attention to our reactions so we can manage to make the choices we prefer. I think all the Bible verses I quoted are teaching variations on that theme, among other things. We have to learn new skills to be new people in Christ. The big difference, as Kreeft pointed out, is always about how we see where we started and where God is in the process. Then we can commit to an understanding of both our joy and suffering. Do they only have the meaning I assign them in the moment? Do they have no meaning at all? Or are they doorways to eternity?